Jim (not his real name) was livid. Six months earlier, he had joined the mid-sized manufacturing company as head of IT with the understanding that his new employer desperately needed to replace its antiquated ERP system. He had also been told that the senior leadership team had identified digital transformation as one of its strategic goals.

“I thought they wanted real change,” he said sadly. “But this was another ‘check-the-box’ exercise. They just want to make things look different without changing anything.”

When he was hired, his employer had described a goal of implementing significant changes that could transform the business. Any forward-thinking professional would jump at the opportunity.

Things were going well for his first six months. Then budget season rolled around. The company cut his CAPEX request in half and directed him to implement an ERP solution that would “make do” at best. In Jim’s mind, the company was not choosing change as he had been led to believe. It wasn’t even chasing change to catch up. It was waving at change as it passed by and placed it on the path to irrelevance.

Jim chose to stand his ground as “the expert” arguing for a more full-functioned, but expensive solution. But the CEO and board stuck with the “make do” solution, and while Jim kept his job his credibility has been damaged and his influence marginalized.

Perhaps you have had the similar experience of being asked to recommend change to solve an important problem and feeling dismissed when your expertise was ignored. If not, chances are you will.

How Change Went Bad

The company’s CEO realized that Jim’s disappointment threatened his long-term effectiveness. He was also a little confused by Jim’s reaction. In the mind of the CEO and CFO, the company was choosing positive change. It was just a different change than the one Jim wanted.

The root cause was misaligned expectations and costs. Jim proposed the ERP equivalent of a Formula One race car. The company’s leaders were looking for a nice upgrade with a little extra horsepower that fit their current budget – something the equivalent of a Cadillac CT5-V.

So, did Jim mess up the project requirements?

Maybe but not exactly.

Jim diligently worked though stakeholder requirements, and the plan he proposed best met those requirements. In addition, he took the job under the assumption that the company fully supported the transformational change they described to him in the interview. When Jim asked about a budget, he was told to design the system that was needed rather than meeting a preset budget.

It became obvious during the discussion of Jim’s proposal that the company didn’t fully understand the current costs for implementing this type of change.

Jim isn’t off the hook either. Asking functional stakeholders to describe the system they would ideally “want” is not the same as asking them to describe the minimum they “need.” Also, in his interview Jim could have gone deeper with his boss to understand short and long-term goals. He could have also asked about the time horizon for making this change. He would have found that the company was operating under a timeframe that made it impossible to recoup the benefits of his proposed investment before its potential sale to another owner.

At the minimum, Jim should have asked the CEO to define what success for the ERP upgrade would look like and how it would be measured. He could have then offered multiple options that allowed everyone to make a better decision.

|

Related article: Choosing Change, Part 1: The essential ingredient to winningBy Randy Pennington |

Another Approach: Resilience and Flexibility

Resilience is not usually listed as a required competency for a CIO. It should be, along with negotiation skills and the ability to build consensus from disparate points of view. Having those skills would have increased Jim’s options to secure the change he wanted, and that would have been best for his employer.

For instance, Jim might have been able to respond to the rejection of his plan with a strategy to build support for it over time. He might also have asked for additional time to rethink and resubmit his proposal based on the current budget requirements.

The absence of those critical change leadership skills left Jim with limited options. He could:

- “Accept the loss,” implementing a solution that he knows will not work and allow his feelings to affect his work.

- Fight back and take a stand for what he believes is right.

- Recognize that this job might not be right for him after all.

Jim chose the first option and is unhappy in a job where he is not delivering the value his employer needs.

How the ‘Choosing Change’ Model Generates Positive Momentum

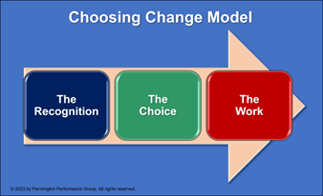

You can help avoid this fate by understanding and applying my Choosing Change model when looking to implement a significant, but necessary, upgrade to your systems or processes. The three steps in the model are:

- The recognition

- The choice

- The work

The power of this model comes from being intentional about the first two steps.

- The recognition: The goal at this step is to eliminate or minimize any surprise at the scope or cost of change and to provide the information needed to make an informed choice. In Jim’s case, this would have meant pushing his prospective employer for more detailed information about their budget and time requirements for the change. It is unlikely that his employer could have answered that question prior to Jim’s accepting the job, but it never hurts to ask. Alternatively, he could have pushed for that information after accepting the job as he was preparing his plan and adjusted his expectations accordingly.

- The choice: The goal is to move beyond the notion that “Change is coming. You must adapt.” In the ideal world, you are choosing whether to pursue change based on its contribution to your purpose, vision, and values. Jim could have worked harder to explain and prove that the benefits of the upgrade were worth the cost. If the company’s time frame was too short to accommodate the upgrade he suggested, he could have been more creative in suggesting ways to stagger the deployment.

- The work: This refers to the time, effort, and money required to implement the new technology and new processes needed to drive the business forward. This is in some ways the easiest of the three steps, but only if you’ve done steps one and two correctly.

I’ve found that the work required to implement change is similar regardless of the resources and effort involved. The real challenge is securing buy-in, overcoming resistance, and creating the momentum for change.

The names and events in this article have been sanitized to protect the individuals and companies involved, but the dynamics are all too real. Let us know whether probing for more information and being more resilient and flexible in the face of objections, has helped you handle such “not really ready for change” situations.

Written by Randy Pennington

Randy Pennington helps leaders deliver positive results in a world of accelerating change. He is a highly sought after resource for helping organizations prepare for their New Next™, and the author of several books, including Make Change Work.